ReConnect Africa is a unique website and online magazine for the African professional in the Diaspora. Packed with

essential information about careers, business and jobs, ReConnect Africa keeps you connected to the best of Africa.

ReConnect Africa is a unique website and online magazine for the African professional in the Diaspora. Packed with

essential information about careers, business and jobs, ReConnect Africa keeps you connected to the best of Africa.

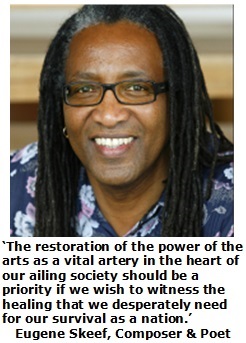

Award-winning South African composer and poet, Eugene Skeef speaks to Sandile Ngidi about his take on ubuntu, South Africa and the need for healing and transformation

Award-winning South African composer and poet, Eugene Skeef speaks to Sandile Ngidi about his take on ubuntu, South Africa and the need for healing and transformation

Eugene Skeef FRSA is a South African percussionist, composer, poet, educationalist and animator living in London since 1980. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, he also works in conflict resolution, acts as a consultant on cultural development, teaches creative leadership and is a broadcaster. In 2003 he founded Umoya Creations, a charity set up to facilitate this international work.

As a young activist he co-led a nationwide literacy campaign teaching in schools, colleges and communities across apartheid South Africa and supported his close friend, Steve Biko.

As well as being at the forefront of the contemporary music scene and collaborating with innovative artists, Eugene has also been instrumental in developing the education programmes of some of the major classical orchestras in the United Kingdom.

This interview followed the release of the video showing the brutal treatment of Emido "Mido" Macia,a Mozambican immigrant and taxi driver, who was killed in the custody of the South African Police Service in February 2013.

Eugene Skeef: Living far from my country of birth for so many years has infused my life with a peculiar kind of pain. We are born to live with pain like a grain of salt in the spice of our lives, but the pain of longing lingers longer than any other pain I have known in my life. Separation from those we love tenderises the soul. All my years away from the fragrance of the fruits of our motherland, the tranquillity of bamboo-shaded rivers, the symphony of birds harmonising with the songs of hope that I heard in the township of my youth, all these memories have served to accentuate the pain of distance from the land of my love.

I was shocked out of my wits, therefore, when I saw the image of Mido Macia being dragged through the street by that police van. I was instantly shocked out of a state of accumulated psychological complacency resulting from the assumed sanctity of our so-called democracy. For are we not the custodians of ubuntu, this collective credo of human oneness that our people gave the world? Was it not to us that the world looked for lessons on how to dissolve the prefabricated walls that separate us from ourselves, and turn them into bridges to bring us back into the sacred place of being truly human?

As the video buffered on my computer screen, I became aware of the pixelated spirit of Steve Biko dissolving into the body of Mido Macia. I was aghast at the sight of these uniformed gangsters shamelessly carrying out an act of such wanton brutality as on that ignominious night in September 1977. But this time the drama was significantly different. This time the principal protagonists were graduates from history’s school of resurrection, and the drama was powered by an insidiously new indifference unfolding in broad daylight and in full view of the public. Was I watching a ritual sacrifice at the altar of the new South Africa?

The narrative communicated by the video clip was a simple one for me to understand: Something is fundamentally wrong when those in whom we invest power through the mechanisms of democracy to protect the citizenry, become predators of the innocent.

Eugene Skeef: We, as a nation, have been resting on our laurels. The intoxication of freedom and the historic emergence of our democracy from centuries of inequity and iniquity combine to make us into a people who feel the world owes us a life of glorious genuflection.

It is not dissimilar to the star football striker who believes that his monetary value supersedes the need to score goals, yet is surprised when his club does not lift the trophy at the end of the season. We need to take stock of our situation and realise that we are no different to any other nation in that we need to work hard, especially in these trying economic times, to sustain our fragile democracy.

The case of Macia also highlights a worrying trend I have been observing in some parts of our country since a few years ago. I have been saddened by what I feel is an increased intolerance of difference in South Africa. In some ways this reflects our still festering history of apartheid. In particular it is important for our people to be educated to remember that a long list of other African countries gave refuge to many of our brothers and sisters who were actively engaged in opposing apartheid and promoting the advancement of the cause of our liberation into a democracy.

The people of these countries fed us and educated us with pride for daring to face the monster and beat him. I despair at the xenophobic attitudes among some of our communities. I have watched, with shame, news reports of attacks on other Africans by some of our people; but I am also fascinated by the colour-coordinated pattern of these hostilities that appear to leave the real masters of South African capital unscathed.

I would say the most important lesson that we can learn from horrors such as the brutal murder of Macia is that a holistic education of the entire nation has to become a priority in getting us out of the cycle of violence that remains the key signature of our society.

In the words of Nelson Mandela, I “believe that South Africa belongs to all the people who live in it”. A civilised nation should protect its people and promote their wellbeing, interests and productive aspirations as its principal asset in its quest for improvement and growth in every sense. I understand this to be the true meaning of a country’s wealth. For what are the real benefits of a country’s development if not the happiness, health, security, prosperity, peace, confidence, shelter and fulfilment of its populace?

Eugene Skeef: Throughout human history, artists have always had the gift of unveiling the light we need as a society to find our way through life’s forest of dilemmas. Artists, then, are like healers. They hold the key to tune the strings of our souls. The poet perhaps benefits from using the medium of words, the primary tool of spoken language. The music of language in the hands of a gifted poet can sing to us and articulate our unexpressed thoughts and feelings. The music of poetry can provide intonation and amplification for our collectively dormant voice.

It is a sad irony that while the rest of the world searches for spiritual and psychic relief in the vast memory bank of our supreme traditional healing systems, we as a nation wallow in a mire of self-denial and self-hate, of which the chaotic state of our country can only be the fruits. The benefits of self-belief – as preached by Biko – to us as a people (and I include all South African communities) are beyond measure. The wealth of our health grows verdant right beneath our feet yet we trample it without due care.

I would say that the restoration of the power of the arts as a vital artery in the heart of our ailing society should be a priority if we wish to witness the healing that we desperately need for our survival as a nation. After all we all know that the arts were an indispensible component of our struggle for freedom.

Eugene Skeef: Any conflict results in destruction, but I believe the more lasting damage lies buried in the cracks between the fragments that we try to glue back together afterwards. Herein lie the invisible human demons that can thrive un-thwarted. Creativity can be a very effective tool in dislodging these stubborn torments.

A more critical effect of my work in that war torn country was siphoning the residual prejudice that I found needed very little spark to re-ignite the dormant destructive energy that people carried around with them.

We know that the history of South Africa is riddled with the cancer of hate, fear and insecurity. I believe many of us also know that the transformation of these destructive feelings within our society, while not an easy task, has to be pursued rigorously to uncover the love buried deep within our collective psyche.

It is the duty of any government that wears a constitutional garland of unsurpassed promise to value above all the cultivation of the wholeness of the soul of its electorate and to place it at the very centre of its shrine. Needless to say, if our leaders do not attain this level of reverence for their people, the vicious cycle of violence will continue unabated.

Eugene Skeef: My call as a proud South African and African to all South Africans and Africans is to cleanse ourselves of the cosmetic stain of self-hate and self-doubt. I implore my brothers and sisters, by which I mean everyone, to wash away the false identities we wear like cheap tattoos and look deeper into ourselves to locate the embedded power of knowing who we truly are in this world.

We must remember that we are the inheritors of a legacy of profound dimensions. We are the sons and daughters of heroes and heroines who did not fear the sun when, driven by the hunger for knowledge, they walked onto the plains of learning. We must honour our forebears by holding our heads high and risk losing favour with those who wedge macabre commercial breaks in the digitised drama of our beautiful lives.

blood on the fields

(for mido macia)

in the land of my forebears

uniformed gangsters

in spit-shone boots

drag living souls

like carcasses of alien beasts

through crowded streets

who are these pleated automatons

who act like un-mothered men

robbed of love

and the joy of childhood

who treat machines of power

like toys usurped

from the abandoned gardens

of their slaughtered puppeteers

what happened to the tongue

that licked the furthest reaches

of my brother’s back

to rid him

of the parasitic tick

has the congealed blood

of our innocence

been washed down

with fermented promises

at the feast of freedom

will the sun rise tomorrow

with the same light

shining on the

impotence of our glory

eugene skeef

Sandile Ngidi is a South African journalist and writer living in Johannesburg.